Welcome to the ‘shed. More than the lake, the watershed holds all of the land, air, surface and groundwater, plants and animals, mountains and lowlands, communities and farms, and people, including their stories and traditions, within its boundaries.

The people

The Hayden Lake watershed, described by many as pristine, is a magnet for more than 4000 property owners, the people who live either seasonally or year-round, and those who visit throughout the year. Many come focused on the lake. But without the other parts of the basin, the lake would lose its luster. Because the lake is a part of a more extensive, interconnected system, it’s important to understand the push-and-pull, the impacts of one area on another, and the relationships between the parts.

The Land

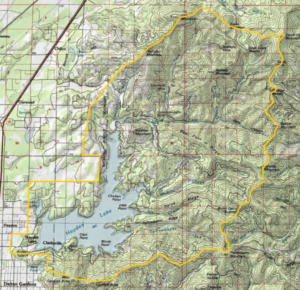

Intrepid journeyers can connect the dots between the hill that rises to the west of Sportsman’s Access, and Hollister, Cedar, South Chilco, Badger, Spades, and Huckleberry Mountains, and Canfield Buttes. From there, toss a metaphorical rope around the southern and along the western shores of Hayden Lake. You will have transcribed the boundary of the Hayden Lake Watershed.

Within a watershed, all of the land drains to a single low point. Yes, stand anywhere within the mapped boundaries. Pour out a cup of water on the ground, and imagine the path that it travels. It may twist and turn, head out and switch back, but gravity will compel it onward until it reaches the low point in the landscape. For the Hayden Lake Watershed, this low point is the lake itself, nestled in the southwest corner of the ‘shed. From there, the land rises north and east in the shape of a tipped-bowl, 64 square miles up-slope from the lakeshore and into the Bitterroot Mountains.

The Water

Water runs off every slope. Every ravine in the watershed’s rugged landscape carries a stream. Your imaginary cup of water most likely ran off the hillside you were standing on and into a creek before it reached the lake. The same destination lies ahead for all precipitation and irrigation water that falls on the land. The two most significant contributors to the lake are Hayden Creek, entering the north end of the lake, and Yellowbanks Creek, which flows into O’Rourke Bay end from the east. All of the seeps, springs, and trickles that join these or any other stream draining into the lake are important for what they move around the watershed: water and silt, naturally, along with chemicals, nutrients, and candy wrappers that land on the ground not-so-naturally.

“Two” Hayden Lakes

Geoff Harvey, a year-round resident on the lake, is known for saying, “Hayden Lake is really two lakes.” When Idaho became a state in 1890, Hayden Creek emptied into the lake at about Henry Point; and water flowed out of the lake from south of Honeysuckle Beach into the Rathdrum prairie. The deep, main body of the lake dominated the landscape. The dike, built on the southern end in 1910, stopped the surface flow of water out of the lake. The water level rose, backing into the low-lying riparian areas like Honeysuckle Bay, O’Rourke Bay, Mokins Bay, and up the Hayden Creek streambed, forming the “new” portion of the lake, the north arm.

Today, the main body of the lake averages 93 feet deep and is 178 feet at its deepest. The north arm of the lake is shallow, ranging from 3 to 10 feet deep. Its lake bottom comprises layers of sediments from ages of mountain runoff overlaid with decades of compost from its turn-of-the-20th-century cattle grazing days. These nutrient-rich, shallow waters are warmer than the deep clear waters of the main lake. And so, the one lake is home to two distinct ecosystems. One is warm and shallow, with a rich source of nutrients at hand. The other is cool and deep, with a less-organic base. So what? Think of what this means for aquatic plant growth, fisheries, and water sports.

The Aquifer

Though the impounded lake no longer sports a surface outlet, it does harbor an important subterranean outlet. That is, it is connected along its southwestern extent, parallel to the human-made dike, to the Spokane Valley Rathdrum Prairie (SVRP) Aquifer via the permeable earth far below the lake bottom. The majority of the lake-bottom is relatively impervious beneath the recently-deposited sediments and gives way to relatively little infiltration. But the moderate area at the bottom of Honeysuckle Bay is filled with sand and gravel from ancient glacial activity. Being porous, it makes Hayden Lake second only to Coeur d’Alene Lake in its contribution to the aquifer.

The Inhabitants

This amazing watershed system offers an equally fantastic myriad of resources to the inhabitants and visitors to the ‘shed. The most populated areas within it lie in a narrow corridor to the west and along a thin ribbon of shoreline around the lake. Over 40% of the lake-front homes draw their drinking water from the lake. The other 60% either pump their water from wells sunk into the water-bearing layers of earth near the lake or receive it from water companies who have tapped into the SVRP Aquifer. Thousands of visitors swim, ski, boat, and fish in Hayden Lake each year. Hikers and other outdoor enthusiasts enjoy the upland National Forest Service lands that comprise over 63% of the land area. Wildlife such as deer, bear, wolverine, owls, squirrel, and more make their homes among cedar trees in wetter areas of the watershed and ponderosa pine in the dryer.

Welcome to the ‘shed. So much more than a lake, this complex, living system is our home, our peace of mind, our hope, our future, our responsibility.